Most Common Mistakes Observed While Canyoneering

In a recent ACA meeting, Pro Master Guide Rick Green from Excursions Of Escalante asked Pro Guides, Recreational Leaders, and Canyoneering Veterans the following question:

Can you think of two or three things that you see canyoneers doing on a regular basis that you would consider to be unsafe or inefficient? All asked were generous enough to give us thoughtful feedback and we appreciate their contributions to this important topic. The following list was compiled, and the ACA presents the “Most Common Mistakes Observed While Canyoneering” list to the canyoneering community. Collectively our goal is to expand all of our knowledge and enhance our experiences together in the canyon.

Here is the list of mistakes in no particular order:

-

- Improper belays. Lack of belays or belaying with poor technique is becoming common. A good belay is incredibly easy to provide and when performed correctly, belay can prevent serious injury or save a life. When done incorrectly, the belayer is at higher risk of falling debris and the rappelled is not really being belayed.

Bad bottom belay

Good bottom belay - Talking around stations. Folks are talking around the rappel and belay stations too much. It should be very calm and focused at both stations (rappel/belay) to create an environment optimal for clear and concise communication. Questions, comments or suggestions that are not pertinent to the rappelled or belayer should be asked at a later time. Catching up with friends while waiting is best done in a safe place that will not impede communication between the two stations.

Less talk and more rigging. Talk about double checking your rigging.

- Too much gear. It’s tempting to bring lots of stuff, but if it’s becoming a clutter of unnecessary equipment, it does open the door for potential problems. Loose items can get snagged, jammed, hooked, etc. while down climbing or when on rappel. Also, over reliance on technical gear has the potential to create a false sense of security for yourself and others. Not saying it does but saying it definitely could.

Can you spot the items that do not belong on your harness gear loop all the time?

- Bad loose rock etiquette. Falling rock is a big risk. People should move around and over loose terrain as a team, aware of each member’s movements. Minimizing hazards by establishing sequencing to get to safety zones should be practiced by the entire group. All loose rocks/materials located by the lead person should be identified and communicated to the group. Climbing above an unaware partner or group can be an extremely dangerous thing to do.

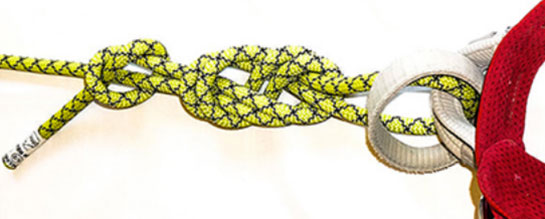

Team member identifies loose rock, communicates risk, and team identifies safety zone - Improper rigging. Rigging is simple. Why are folks struggling with this? Rig it releasable, ensure it’s retrievable . . . go to work. If you are into “ghosting” or static rigging, stick with experienced partners or have a plan to lower folks down when some gear gets jammed.

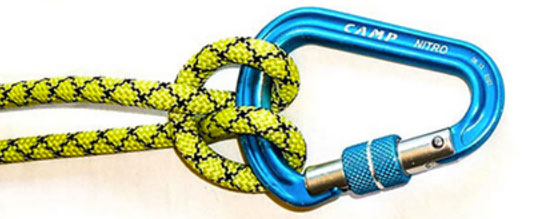

Cut bad rigging and re-rig - Minimal partner checks. Initial partner checks while gearing up, plus secondary checks at each rappel station should be standard. It’s simple to position a person at rappel stations to check individuals for harness doubleback, locked biners, and loose gear. You’ll be shocked at what you see. Hanging out at the rappel is a much appreciated role, too. You reach over and lock the unlocked gate of a friends carabiner or point to a harness not doubled back, and they look at you like you just saved their life. Which you may have just done.

Team member checks anchor and rigging, you check harness, helmet straps, descender rigging, locked biner, gear check. - Anchor inspection, back-up, and testing. Anchors should be inspected every time. Abrasion points, knots, and impact areas (from flood debris) need to be inspected every time. Back it up with a top belay, test with someone big. If it fails, stop and reevaluate.

Inspect rock, bolts, hangers, webbing

Test before rappelling down!

Marginal anchor? Sequence it, test it, back it up

- Poor sequencing of ropes/people. Proper sequencing of equipment and assessing human skill sets contributes to the overall safety and experience of the group. Gear and human skill sets is so important.

Partner sequencing: Tall heavy team members first, light team members last.

Team member moving at the front of the group ahead down canyon. Has rope? Ready to rig and set anchors? Good vs. Poor sequencing - Not spotting. It is improving over the days of “don’t touch me” or “I’ve got this” (annoying). The best canyons are done as a team, using partner captures, human ladders, and spotting.

Spot your partners - Jumping. Unless you are landing in water whose depth has been checked and is sufficient for a safe landing, jumping is really a bad idea. It’s much better to do a belayed downclimb, get lowered or use a hand-line. The “penalty points” for jumping not only apply to you, but to the entire group. If someone sprains an ankle (or worse) on a trip, the whole team will suffer. Jumping is bad form!

Was that pool deep enough to jump? No.

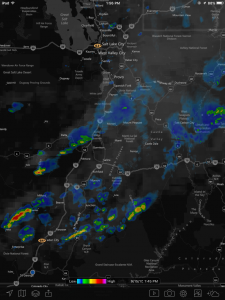

- Overreliance on beta. Location, technical ratings, conditions, exits, weather…some of these things can and do change. It is a good idea to rely on sound judgement and common sense when you are in a wilderness environment and not rely solely on what the weatherperson has forecast or what someone “posted” on the internet. Also bring a good map and compass, electronic devices can get wet and become in-operational or end up in an unretrievable location.

Learn to work with topo maps, coordinates, bearings, scales.

Learn to read weather forecasts.

- Improper belays. Lack of belays or belaying with poor technique is becoming common. A good belay is incredibly easy to provide and when performed correctly, belay can prevent serious injury or save a life. When done incorrectly, the belayer is at higher risk of falling debris and the rappelled is not really being belayed.